Summer has begun its ebb. Do you feel it? Not quite perceptible, the start of autumn is like smelling a change in temperature. It's still hot and humid, yet we register a difference at the overlapping edge of our senses. Perhaps change usually has this character because it resides just beyond the human scale of things, like the climate or evolution. We cannot see the mountainside erode, but somehow we sense it nonetheless.

Change seems constantly on my mind: political change, climate change. And tucked away, sex change. It's my experience, after all.

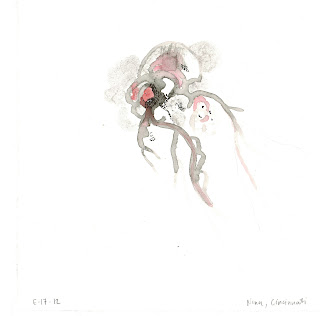

Like a storm's energy before its bright beaks of lightning and fisted thunder, sex's transformation starts imperceptibly. In general, we pretend sex is obvious, some reductive algebra of chromosomes and physiology, but as we've slowly come to realize, sex is many processes that include X and Y chromosomes, hormones, gonads, internal sex structures and external genitalia, as well as history, culture, environment and other variables still to be named.

Excitingly for some, unnervingly for many and boringly for others, sex remains unfinished indefinitely. So, what does changing sex mean when sex is continually changing?

First and most important, it's a misunderstanding that changing sex is about crossing—as the prefix "trans" in "transsexual" supposes—from one sex to another. Of course it can be, but more often the starting point is subtler. For example, a man assigned at birth as female never felt female for emotional, situational, chemical or even biological reasons, and he grew up disidentifying with his assigned sex.

He has always felt un-female and un-woman. Here, female-to-male is somewhat of a misnomer because he is not necessarily crossing sex. Rather he is undergoing something closer to transsexual-to-male, or indeterminacy becoming more indeterminate.

But as Canadian filmmaker Chase Joint describes in his piece "Post-Transition: Who We Might Be," this man can share his experience only by simplifying his experience to his family and health care providers, even to sympathetic friends and allies.

Or worse, he has to convince detractors with unwavering confidence that he is happily a man and better for it. Every movement of his body, from posture to sneezes, is self-considered because he is keenly aware that people habitually sex these things. Can you imagine the fatigue of becoming more of yourself, attending to the ongoing changes of yourself, while having to shore up a narrative that doesn't belong to you and flattens your experience?

Like the change from summer to autumn, changing sex is more than a conscious choice or an act of will. It may be that change comes on a scalpel of desire or along a hormonal riptide, such that the body is legibly sexed, but this describes only a fraction of what is at play.

Hormones, for instance, have ranging impacts. Taking estrogen can cause fat deposits to uproot and travel to new sights of colonization so that hips widen, breasts grow and lactate, and musculature softens. Estrogen can also alter the eye's structure, affecting vision. It can modify the body's heating and cooling and olfactory systems. I remember sitting on a subway train, feeling so disoriented by smelling layers of place, saturated funk and perfume that I got off the train and walked six blocks to my stop.

Estrogen has health consequences. Annual mammograms and regular breast exams are recommended for transsexual women. If, like me, you started hormone therapy with Premarin (complemented with progesterone), derived (wickedly) from horse urine, how much of that early transition was about becoming horse-like? And later still, with soy- and yam-based estrogens, vegetal? Hormones are a complicated business, and they're just one plot line in the relentless narrative of sex.

Transsexuality not only is more nuanced than it is typically described, it breaches the defended territories of sexual reproduction. Thomas Beatie became a national sensation as "the first married man to give birth." Although other men gave birth before Beatie, he was able to capitalize on curiosity and voyeurism, an irresistible tipple, and start a public conversation about the limits of sex: "How can a man have a baby?"

And now, with the first successful uterine transplant, in Turkey, and Britain and Sweden following suit, it's only a matter of time before other wombless bodies have wombs. But surgical interventions are not alone in transforming our assumptions about sex. Infants are being breast-fed by all kinds of lactating men and women. And last week, a friend sent me a photo of her "false pregnancy," in which the endocrine system produces hormones that physically express as pregnancy. She is a woman "with a transsexual past," as she would say, and still her body is compelled to reach beyond her history. Sex changes; remarkably and unavoidably. Sex is an unending process, not yet finished with any of us.

Sex is changing, and so is transsexuality. Many men and women with trans histories occupy restricted areas of sex. Others are questioning the past tense of "transitioned"—what Chase Joint calls "post-transition." Moving toward your self through your body is less about a horizon in which change stops than about how to embrace the endless process of change.

It is hardly easy; change requires openness to uncertainty and a willingness to tell the story differently. For all of us—trans or otherwise—sex is reinventing itself just as we reinvent it. So the question is how do we—all of us—take to heart the unchartered dimensions of change? We can practice, as summer becomes fall. Trees begin to turn as photosynthesis slows down. Earth tilts toward itself, finding equanimity with the sun by late September. In doing so, the Earth transfers force and energy through its complex systems, unleashing seasonal potentials in already changing processes. Then, soon, winter ...

This article appeared in print with the headline "Changing attitudes about changing sex."